|

MRS. ROYCE'S AND MISSES PATTENS': RIVALRIES TO AGITATE

By Carol Huber

I think it is safe to say that silk embroideries have now been accepted, and declared their rightful place, in

the world of decorative arts. So much so that they are now highly sought after and command the attention of serious

collectors of both needlework and furniture. After all, the men who purchased the fabulous antique tables, chests,

chairs etc., all sent their daughters to expensive schools to learn the art of embroidery which they proudly brought

home to be hung in the 'best' rooms.

Part of the fun in collecting is learning the history of the period in which objects were made. Imagining what

life was like at the time, reading and researching. With this in mind I would like to share with you a passage

I have always found fascinating from, "The Memorial History of Hartford County Connecticut 1663-1884",

edited by J. Hammond Trumbull, President of the Connecticut Historical Society in 1886. It is a little window on

the past and gives us a sense of the importance of embroidery in the curriculum.

"The school which attracted most attention and educated a large number of girls, before 1820, was established

by Mrs. Lydia Bull Royce, about 1800….Of this school we have a very graphic sketch in a letter from Rev. Prof.

J.J. McCook of Trinity College who married a granddaughter of Mrs. Royce…

'While making a call upon Miss Rockwell, who lives in one of the oldest of the old houses in East Windsor Hill,

I noticed upon the wall an "Aurora" done in water-colors and of a style and proportions which at once

recalled one in my wife's possession,--the work of her grandmother, Mrs. Lydia Royce. Upon inquiry, I found that

the resemblance was not accidental. Miss Rockwell's elder sister, now long since dead, had been a pupil in Mrs.

Royce's school more than sixty years before. From Miss Rockwell I learned the following…

'After learning all that the academy on the hill could teach them, the best families, it seems, were accustomed

to send their daughters to Mrs. Royce's, in Hartford, for a finishing course. Miss Rockwell's sister was sent just

as the school was about to break up on 1817. But she recalled the names of several of her girl-friends,--Ann Watson,

Frances and Maria Bissell, Helen and Ursula Wolcott,--names still well known in the locality, one of them historical,

who were there as early as 1810. One of them, Miss Maria Bissell, she remembers, came in one day, and said, "Now

look, Henrietta and I will show you how Madame Javet dances;' and thereupon capered about the room, executing some

of those grandes manoeuvres which must have made the dancing of the period such a fearful and wonderful sight.

This Madame Javet, then, was one of the teachers in Mrs. Royce's school, and her name suggests what I have heard

from my cousin, Miss Sheldon,--Mrs. Royce's granddaughter,--that she had understood that there were among the teachers

members of the families of certain French emigres driven from their country by the events of the Revolution, and

here, as in every country to which they came, finding in teaching a resource when all other resources had failed.

The 'accomplishments,' which then made a large part of female education, when education was given at all, were

naturally confided to them. Not all the accomplishments, however; for Mrs. Royce herself taught drawing, painting

and needlework. The walls of the Rockwell parlor are covered with paintings done under her instruction. In addition

to the subject above alluded to, I observed a 'Ruth and Naomi,' of the usual sentimental type' a 'Cybele' driving

a team of lions hitched to a gorgeous chariot, herself more gorgeous still, the fierce grin of the lions in striking

contrast to their lamb-like and somewhat wooden attitude,--Cupid sits in front and holds the reins; the 'Arch of

Titus,' a fair likeness; finally the 'Romps,' where a lot of oddly appareled, old-fashioned looking little girls

are surprised in the midst of a jollification by their school-mistress, the very frills of whose monstrous cap

seem to fling out their folds in horror at the enormity they are forced to witness. In the foreground is the ringleader

of the malefactors, standing demurely by the side of an overturned writing-table, her hands and apron all covered

with ink stains, of which the floor, too, has received a plentiful share. Miss Ursula Wolcott, upon whom I called

after leaving Miss Rockwell, showed me, with mild pride, a piece that she had done at the school. It is the 'Parting

of Hector and Andromache,' with the customary accompaniments of tents, warriors, and weeping Astyanax. This is

in needlework, very beautifully done; only the faces are painted in. Work of this latter kind seems to have been

done by Mrs. Royce's own hand, as a charge in one of Miss Wolcott's bills seems to show. (The bill to Major Woolcott

totals $47.33 includes tuition, board, supplies and $5.50 for Painting Picture. See, Girlhood Embroidery, by Betty

Ring, p.212.)

'The bill, now yellow tiwh age, is folded carefully for filing, and on the back is written, no doubt in the Major's

hand, 'Miss Royce Bill for Suley.

'She is still 'Miss Suley.' And, though now sixty-six years distant from her girlhood, has not lost the gentle,

agreeable manners, the cultivation of which formed, no doubt, one of the most important items in the school curriculum.

'The old lady could remember but little concerning the course of instruction, except for painting and needlework,

her memory one the subject had not been roused for so many, many years. Miss Rockwell, not having attended the

school, knew nothing definitely on this point. She only supposed that they taught reading, writing, arithmetic,

and geography, with French, dancing, painting, and needlework; and she remembered specifically that Mrs. Royce's

school was 'far ahead of the Misses Pattens.' From which it is apparent that rivalries and emulations may have

existed even at that remote period to agitate if not disturb the reputed tranquility of educational circles.

'Its celebrity, in fact, seems to have been such that pupils were drawn to it from a considerable distance. Miss

Rockwell mentioned the names of several from other States than Connecticut; and since the room for boarders was

always limited, the majority of these pupils appear to have occupied quarters in the town, and to have attended

the classes along with the day scholars.'"

The account of the school given here gives us an insight into the importance the role of embroidery played in the

wealthier and educated families of the period. The rivalry between the Patten and Royce schools was such that it

was recounted sixty years later by a woman who had attended neither one. This telling also describes the classical

scenes that were translated to stitchery implying that the girls were familiar with the literature their pictures

represented.

The last ten years have brought much recognition to the field of silk embroideries, due largely to the knowledge

base that has been greatly expanded and the subjects and prints of many of the pictures identified. Collected and

cherished they have come full circle and once again hang in the 'best' parlors and rooms in America.

Silk embroidered picture showing a scene from the poem ‘The Hermit’ by Thomas

Parnell, and the print by Benjamin Tanner. Painted portions by Lydia Royce. Silk embroidered picture showing a scene from the poem ‘The Hermit’ by Thomas

Parnell, and the print by Benjamin Tanner. Painted portions by Lydia Royce.

Silk embroidered picture depicting the Biblical story of 'Jeptha', c.1810.

Worked in lustrous silks, metallic thread and appliquéd fabrics on dress and foreground-a signature of the

Lydia Royce school, with painted faces and background by her. Silk embroidered picture depicting the Biblical story of 'Jeptha', c.1810.

Worked in lustrous silks, metallic thread and appliquéd fabrics on dress and foreground-a signature of the

Lydia Royce school, with painted faces and background by her.

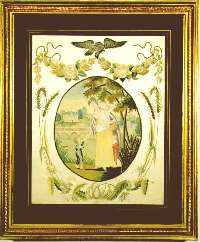

Silk

embroideried picture worked by Louisa Bellows at Misses Pattens’ School, c.1805-1810. Silk

embroideried picture worked by Louisa Bellows at Misses Pattens’ School, c.1805-1810.

Silk embroidered picture worked at the Misses Pattens’ School depicting Charity.

c.1810. Silk embroidered picture worked at the Misses Pattens’ School depicting Charity.

c.1810.

|